Air Drain – Mind the Gap

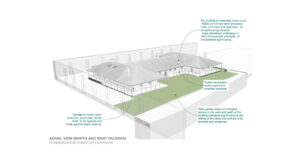

Not the most thrilling topic of conversations but nevertheless an important one that needs to be had when it comes to working with old buildings. The principles are simple, the solution is simple (on paper), but the realities and practicalities when dealing with buildability, cost, and sensitivity of adjacent building fabric is a tricky one. The textbook and ideals are the starting point, but to work out an elegant and workable solution takes time and experience, with the outcome worth sharing. This was the scenario at the old Hospital at Fremantle Prison, completed this time last year, where some sound and lateral thinking was required on detailing a much needed air drain to the building perimeter.

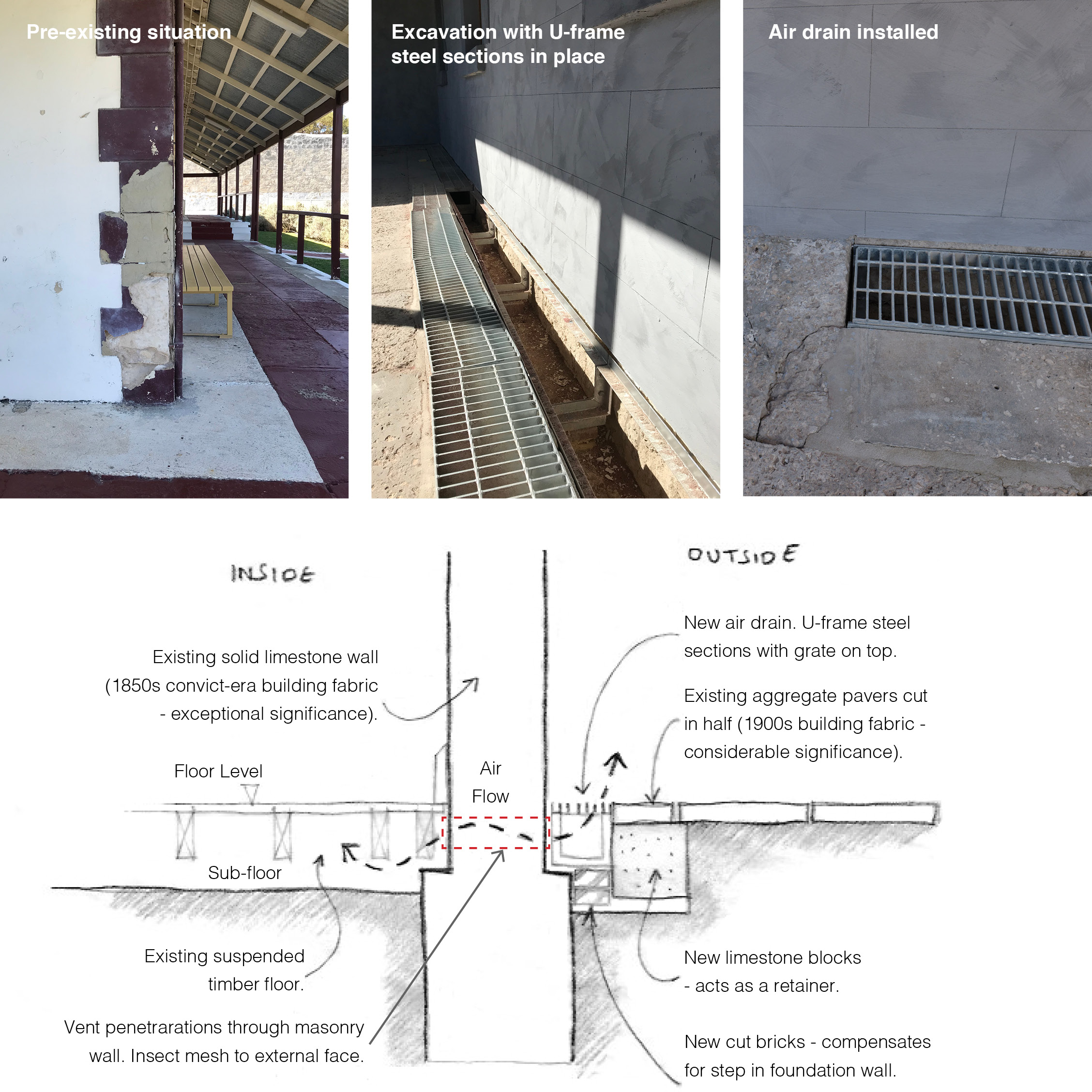

The original convict-era limestone walls dating back to the 1850s are solid but of relatively soft and porous material that allows moisture and salts to readily travel through the path of least resistance; manifesting itself in the most unwanted areas. With nowhere to go, as the outside flooring was hard aggregate pavers, this moisture was getting trapped within the timber sub-floor and in the walls. The intrusive wall finishes of acrylic paint and cement render exacerbated this problem, but this was dealt with separately by simply removing and replacing with breathable finishes. The fundamental issue was the floor and walls below ground needing to ‘breathe’ to prevent further decay of significant building fabric.

The simple instinct was to build a trench around the building perimeter to create the air drain and place a grate on top to bridge the gap whilst allowing air flow to permeate through. Sounds easy, but how do you achieve this in a sensitive manner with as little intervention as possible? Removing the strip of aggregate pavers along the building edge, excavating the trench, and building a small retaining wall was the first thing required; but not in concrete – who’d want to introduce such a modern hard material in this situation? Instead, limestone blocks were chosen to form the trench and also support the edge of the aggregate pavers, with every second paver cut in half. This was a resourceful solution by the Structural Engineer, Peter Baxendale, as it kept some of the original pavers dating back to the early 1900s, intact, and able to be used elsewhere on the project. Penetrations were made periodically through the masonry wall to vent the sub-floors of each individual room into the air drain, which were sealed with insect mesh to the external face. With the trench and retaining wall solved it was a case of how to support a steel grate along the top without fixing back to the original limestone wall – to be strictly avoided. A solution to use welded u-frame steel legs embedded in the same mortar used for the limestone blocks was implemented, with a simple steel grate sitting on top to complete the air drain – wow, fantastic, all solved – air flow, little intervention, and a neat outcome too.

A deviation of the detail had to occur when it was realised (whilst on site) that there was a step in the foundation wall half way up the face of the trench. This led to a reduction in height of the air drain and the introduction of recycled bricks to support the U-frame legs. With the air drain being protected and undercover from the verandah, this avoided the need to address any stormwater collecting in the drain. With regards to maintenance, all that is required is the top steel grates to be periodically removed to clear away any debris and ensure ventilation holes to the internal sub-floor are kept clear.

There was a design oversight to look out for which was the steel grates running past door openings, which became an issue for high heels getting trapped! Anti-slip tread coverings had to be retrofitted over the grates to these areas to compensate for this, which all in all wasn’t too bad – MIND THE GAP.